This article originally appeared at Ammoland.

For this NRA High Power F-Class competition, I used this Masterpiece Arms BA Lite PCR Competition model chambered in 6.5 Creedmoor.

What’s hotter than Captain Gastroplasty at a Texas Chili Cookoff? Long range shooting that’s what.

While we throw around the term ͞Long Range Shooting like it’s a discrete sport, it’s really a collection of multiple games of varying styles. Sure, they all have extended distance in common, but beyond that, the styles diverge. At risk of offending everyone, I might describe long range shooting as two general types of disciplines.

- The methodical and precise ballistic science game. That would be NRA High Power F-Class Shooting.

- Running, gunning, and math-based winging it. That would be PRS or Precision Rifle Series.

So let’s clarify those two very broad and probably unfair generalizations by taking a look at these two long range shooting sports. Just to be clear right up front, both rely on shooter skill and consistency, they’re just different regarding which specific skills are most important

Last weekend I had the opportunity to compete in my very first F-Class match. I’ve done lots of long range shooting in all sorts of flat and mountainous conditions out to about 1,500 yards, so I wasn’t overly concerned about my ability to land at least a couple of rounds in the same zip code as the target. On the other hand, I expected I’d be facing a bunch of grizzled veterans who know this particular game inside and out. As it turned out, both expectations came true.

F-Class is always shot from the prone position, making it a great way for new(er) shooters to get involved.

The match was held at my local shooting facility, Palmetto Gun Club. Carefully checking the online information in advance, I saw the magic words – “Bring what ya got. Come out and shoot!” You see, like most shooting sports, those grizzled veterans like to win, but most of them like to help rookies get involved even more. I quickly determined that there are two classes for NRA Long Range shooting: Open and F/TR. If you choose F/TR, you have to shoot either .223 Remington / 5.56 NATO caliber, and you’re limited to total rifle weight of 18.15 pounds including optics, bipods, and such. You also have to shoot using a sling and/or bipod – no fancy ground-based shooting support devices allowed. On the other hand, if you want to just give the sport a try and you don’t have a suitable service caliber rifle handy, you can simply enter Open Class. That allows any caliber up to .35 and you can rest your rifle on just about anything.

The 800-yard targets are the ones you can barely see on the right. The row towards the left are just 200 yards.

I have a loaner rifle in from Masterpiece Arms chambered in 6.5 Creedmoor that will shoot a mosquito off a gnat’s elbow, so I chose to enter Open Class. While I could have used a stationary support rifle rest, I simply added a Caldwell Bipod up front, topped the Masterpiece Arms BA Lite PCR Competition Rifle with a Burris Veracity 4-20×50 optic and proceeded to load up some ammo. I had a couple of boxes of Sierra’s 130-grain Tipped Matchking (TMK) .264 bullets, so I cranked up my press and made a hundred carefully constructed rounds.

Since I hadn’t shot this particular combination of rifle, projectile, and optic before, I did some advance ballistic planning using Ballistic’s AE smartphone app. After entering some basic information about the projectile type, velocity from the MPA rifle, scope height, zero distance, and atmospheric conditions, I determined that my bullet would drop exactly 14.89 feet over the 800-yard distance set for this day’s competition. That works out to exactly 21.33 minutes of angle. On the Burris scope, 85 clicks brought me pretty darn close.

While they’re big up close, these targets get kind of tiny at 800 yards.

The elevation or bullet drop part is pretty easy to deal with because gravity is constant. If you put in good numbers, a ballistic program will tell you exactly what adjustments need to be made to get you close to the bullseye, at least vertically. You’ll have to fire a few test shots to account for slight variances in scope precision and such, but that’s fairly easy and unless you have a terrible scope, you’ll be close to start.

The hard part is accounting for the wind. Your ballistic program can also tell you how much your specific bullet will drift based on the wind direction and speed. As an example, the load I used at 800 yards will drift just under 53 inches SIDEWAYS with a 10 mile per hour crosswind. Fortunately, we only had to deal with one to three mile per hour winds coming from the ten to eleven o’clock position that day. As the wind varies shot to shot and can be completely different at any point between shooter and target, wind estimation ability is the skill that separates the rookies from the pros. Even with our very mild conditions, the wind alone could move your shot about three inches give or take. When shooting rifles capable of four-inch groups at 800 yards, that puts the burden on the shooter as much as the equipment. Only only does your sight picture and trigger press technique need to be precise and consistent, you need to make a really good guess at what the wind will do to each and every shot.

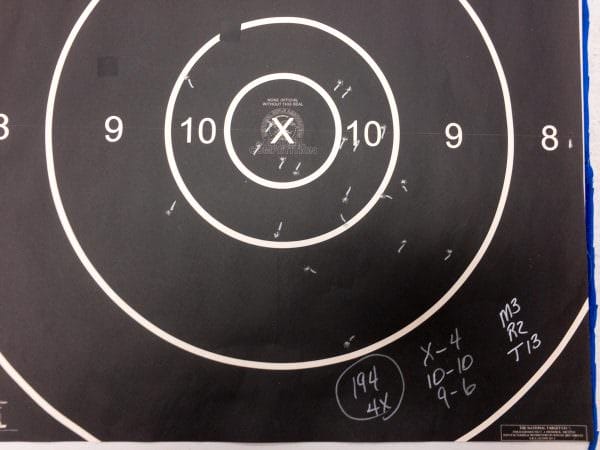

I was happy with this result. As you can see, I didn’t fully trust the degree of the left to right wind, so my group favored the right side of the target.

So let’s try to sum up the key points of the NRA F-Class long range sport. You can get started with most anything you already have because the Open Class has a lot of leeway regarding rifle and caliber. You can even start with store-bought ammunition. Got sandbags or a bipod? Then you’re good to go from a shooting rest standpoint. Since F-Class deals with known ranges and target size, many repeat competitors quickly start to optimize equipment. To get the most out of your rifle, you’ll soon want to reload your own cartridges. You’ll also want a purpose-built scope that offers somewhere above 20x magnification with great clarity and a fine reticle for precise shot placement. Oh, NRA F-Class doesn’t allow muzzle breaks or suppressors, so be sure to just use a standard thread protector if your rifle has a threaded barrel. If your rifle has a flash suppressor installed, I doubt anyone will give you any trouble, but you might find your rifle will shoot better groups if you remove it.

The bottom line is this. If you enjoy precision and tinkering, F-Class will be a great sport for you. While skill is always the ultimate determinant for collecting medals, the right equipment will help you get there too. At your first match, you’ll see all sorts of accuracy enhancing gizmos. If you enjoy playing the equipment game, then F-Class might be for you.

The other major style, Precision Rifle Series, is a bit more like tactical golf with time limits. Competitors have to engage multiple targets at varying distances, and from unusual positions, while the clock is running. You might find yourself shooting from a rooftop or from behind common environmental barriers. While you have to have equipment up to the task and know your ballistics, there’s a lot more emphasis on speed and adaptation to different target scenarios. We’ll take a closer look at PRS in a future article.

Leave A Comment