This article originally appeared at Ammoland.

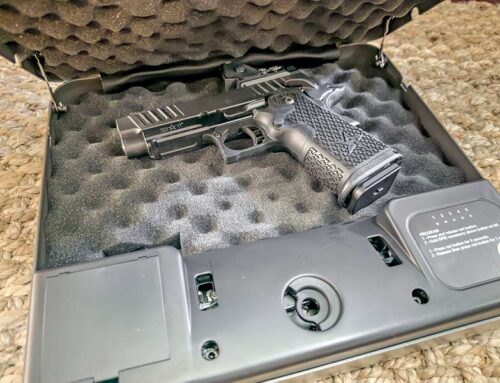

For this drill, I like to start in this position. It’s basically the portion step in a draw where the support hand joins the firing hand.

Normally Hollywood movies dish out useful gun advice about as often as the sun goes out, but every once in a while, a movie presents a surprisingly relevant learning opportunity.

Take that corny 1980’s movie, The Karate Kid, for example. I’ll spare you the whole storyline, but in case you never saw it, here are the relevant plotline elements:

- After getting triggered by Karate bullies, main character and overall snowflake, Daniel (The Karate Kid) decides that he wants to learn how to be a martial arts butt kicker.

- He enlists the help of the Bruce Lee of local apartment maintenance guys, Mr. Miyagi.

- Daniel shows up at Miyagi’s house for training and is immediately put to work waxing Miyagi’s cars and painting his wood fence.

- After hours, or maybe minutes, of painting and waxing, Daniel get’s cranky about being Miyagi’s manual labor b&tch, until he learns a valuable lesson.

To understand Daniel’s epiphany, you have to know that Miyagi made his little Karate student helper wax and paint using very specific, and kind of weird techniques. The car waxing required the “wax on” to be done with a circular arm motion in one direction. “Wax off” was the same motion in the reverse direction. As for painting, that required a full-arm brush stroke all the way up and all the way back down, kind of like painting a line from his knees to some point over his head.

I’m all in favor of practicing the complete draw to first shot sequence, but you can’t always do that at every range.

Young Daniel-san whines, grumbles, and complains until he finally confronts the Mr. Rogers of Karate teachers, demanding to know when he can start to learn some sweet martial arts moves that will impress the chicks rather than doing Miyagi’s chores. Without warning, Miyagi launches a series of punches at our young waxer-painter. To his great surprise, Daniel-san finds himself effortlessly blocking the attack using, you guessed it, the very same waxing and painting motions he’s been repeating over and over on the cars and fence pickets. The proverbial light bulb goes on, and Daniel realizes that his apartment-dwelling Samurai has been teaching him the basics of self-defense movements by developing subconscious muscle memory. When his brain detects an incoming punch, there’s no need for thought; his arms are already pre-programmed to move in response.

Repetition and muscle memory apply to a whole slew of important life skills like separating Oreo cookies, hitting the brakes when the idiot in front of you is busy texting, and yes, shooting a gun. Let’s look at a way you can ramp up your subconscious skills using the Hollywood-certified Karate Kid method.

This little practice routine I use doesn’t have a cool tactical name, so let’s call it the first shot on target drill.

To me, the slowest part of getting a shot off from a concealed carry position isn’t the motion of drawing; it’s getting the gun into a perfect sight picture and ready to fire an accurate shot. Grabbing an object (a gun in this case) is a pretty natural motion. We grab things like keys and cell phones all the time, so snagging a gun from a holster isn’t an entirely foreign physical action. Don’t get me wrong; it’s essential to practice your draw over and over and over. All I’m saying is that the motion isn’t unnatural in the scope of things, so it comes easily to most people. What is unnatural is raising that handgun to eye level and bringing your focus back to the front sight while at the same time lining it up with your intended target. In fact, that’s kind of opposite from what our brain wants to do – focus on the target – so some Karate Kid reprogramming is in order.

When most of us get to the range to practice, or even when we dry fire at home, we tend to aim the gun at the target and focus on hitting it repeatedly. Make no mistake, that’s important, but keeping the gun on target during most of your shooting session ignores the whole process of raising your gun to the target and getting a fast and accurate sight picture for that critical first shot. Your results will almost certainly vary, but when I break the draw, aim, and shoot components into sections and observe each with a shot timer, the slowest portion is raising the gun to eye level, getting a precise sight picture, and shooting. And if I break that up, most of the time I spend is acquiring the sights against whatever target backdrop at which I’m aiming. Stated differently, I can draw and get the gun to approximate eye level faster than I can precisely align the sights once it’s there, especially when shooting at a target that doesn’t contrast well with iron sights. Try shooting at dingy, unpainted steel plates with iron sights and you might see what I mean.

With that said, here’s a practice routine that’s really helped me improve my ability to get an accurate first shot off quickly. The best part is that you can do it via dry fire at home or at the range. Maybe it will help you too.

- Start from a low ready position with a two-handed grip and the muzzle pointed down range. Try to replicate the position where your gun would be right as you joined your support and firing hands during the draw stroke. The gun will be somewhere around belly level and pointed down range.

- Now, very slowly and very deliberately, raise your gun while extending into your preferred shooting position. Whether you use the Isosceles, Weaver, or the Weaver’s second cousin twice remove stance is entirely up to you.

- Focus on your front sight as the gun elevates into the shooting position.

- Ideally, your front sight, rear sight, and the target will all come into alignment just as your gun reaches the ideal firing position.

- Just as sights and target align as your gun reaches the perfect firing position, slowly and deliberately break the shot, focusing on a perfect trigger press.

- The goal is to make the raising of your gun, picking up the sight picture, final sight and target alignment, and the shot one smooth and continuous motion.

- For starters, just fire a single shot just as the sight picture becomes perfect.

- Repeat.

The idea is to be ready to break and accurate shot as soon as the gun hits normal firing position.

The idea is to create a smooth and continuous motion that brings the gun into position while the shot is broken without pause to “aim” as your arms extend into shooting position. Continuity of motion is the goal of this informal exercise. Rather than frantically drawing your gun, then figuring out how to get the sights on target once it’s raised, you’re doing both simultaneously in the same motion and firing the shot at the instant the gun reaches final firing position.

There are are a few keys to success.

- You’re building muscle memory, so it’s important to do the motion exactly the same each and every time. If every draw, sight picture, and shot iteration is a little bit different, you’re not “programming” any waxing or painting moves.

- Go slow. Again, perfection and consistently of movement is what you’re going for. If you train your arms, hands, eyes, and brain, in slow and consistent motion, speed will take care of itself when the time comes. Trust me on this. Hey, it worked for the Karate Kid, right?

- Focus on keeping the sight alignment perfect while raising your handgun. If your front sight elevates to the point where you have to bring it back down to get on target, you’ve wasted motion and therefore time. Think of the front sight rising to the target, but not moving above it.

- Ideally, the movements of raising your gun into position and aligning the sights will be perfectly synchronized, with both reaching their perfect state at the same instant.

Depending on the type of handgun you use (double-action, striker-fired, single-action, or manual safety) you’ll want to think through the ideal time to safely disengage the safety (if applicable) and put your trigger finger into position. Of course, that assumes you’ve made a conscious decision to fire. Whenever you choose to engage the trigger finger, do it the same way every time and only when the gun is pointed down range.

Normally I might issue a “spoiler alert” warning, but since it’s a 30-year old movie, tough noogies if you haven’t yet seen it. Daniel confronts his bullies, and all that weird car waxing and fence painting allows him to beat up his much bigger and meaner adversaries at the big city-wide Karate competition. He might even get the girl, but I don’t remember that part.

So, if you want to be a better shooter, be like the Karate Kid. Do this a hundred times or so over different practice sessions and I guarantee you’ll be amazed at how quickly your first shot can hit your intended bullseye.

My God, did anyone try to edit this before posting?

That is an old Japanese story. Student goes to the mountains to learn swordsmanship from a very learned monk. The monk sets him to cleaning the toilet (old Japanese toilets were really nasty. Think the porta-potty in Yosemite Valley in August.), cooking, washing clothes, making meals, all the while beating the student with a stick every time he makes the slightest mistake or doesn’t do everything just exactly the way the master tells him. The student keeps asking the master when he is going to learn swordsmanship. The master keeps telling him he’s not ready yet. One day as the student is making tea he feels the master’s shadow fall on him and he puts up the teapot lid and blocks the blow. The master say, “Now you are ready.” The zen philosophy was if you have to think about your technique you have lost before you touch your sword. It really is true. You must practice your technique over and over and over until you don’t even think of it. Your mind must be totally blank. If you think, “I’ve got it.” you don’t. I don’t remember who the director of the Karate Kid was, but some Hollywood directors have studied Japanese literature and, especially, Japanese movie directing, especially from the hayday of Japanese movie making, the 1950s and 60s. Rashomon, Seven Samurai, all of Kurosawa’s movies, etc.

real quick synopsis.

MUSCLE MEMORY.