This article originally appeared at Ammoland.

About three years ago, I had the pleasure of visiting the fledgling Sig Sauer Ammunition factory. When I say that it was in the middle of a corn field in the boondocks of Kentucky, I’m not at all exaggerating. It was actually in the middle of a farm. A few dirt roads and you were there. As the business took off as a result of the company’s fanatical dedication to quality and consistency, it didn’t take long to figure out that a bigger, much bigger, factory was needed.

I recently visited the brand-spanking-new Sig Sauer Ammunition facility just outside of Little Rock, Arkansas.

Here’s an inside look at how Sig’s ammunition is made.

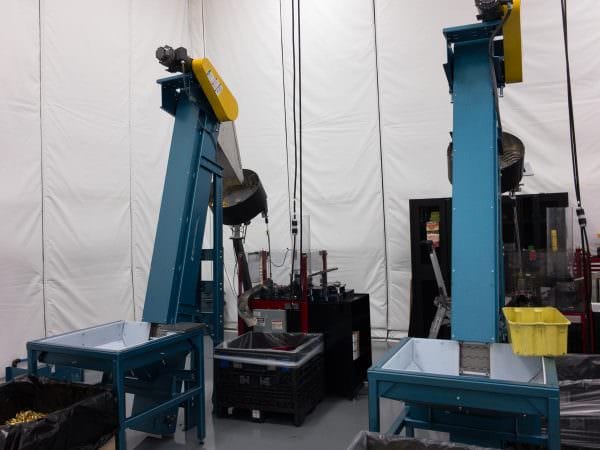

Part of the automated ballistic gelatin making system.

The folks at Sig Sauer Ammunition are serious about product performance. To verify that new designs do what they’re supposed to and that lots of ammo perform up to design standards, the company operates a dedicated testing facility inside of the main factory. As I recall, the Sig folks go through more ballistic gelatin than anyone in the industry, even more than companies with much larger production. As a result, they’ve developed a custom setup to make ballistic gelation blocks literally by the thousands. The system monitors ambient and water temperature, measures precise amounts of powdered gelatin, and cranks out from one to 12 blocks per batch. A little cinnamon oil prevents spoilage from the animal-based gel, but even still, blocks are always either used or thrown away within seven days.

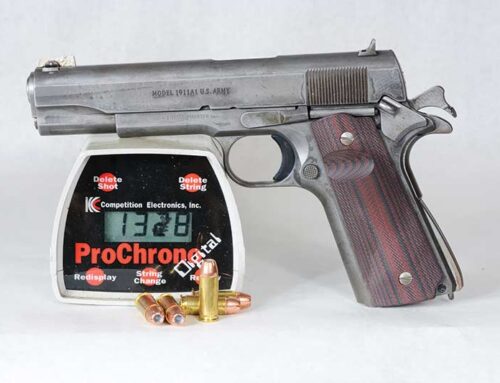

One of the indoor ranges used for velocity, expansion, and function testing.

The company houses several indoor ranges for testing. In the picture here you might notice that the bullet trap looks darker toward the back. That’s because a water system keeps it wet to prevent dangerous dust and residue from getting into the air. Sophisticated chronographs verify that velocity is up to spec and semi-permanent fixtures are used to perform testing in ballistic gelatin using a variety of scenarios including bare gelatin, light fabric barrier, heavy fabric, wood, steel, and automotive glass.

Dedicated priming machines.

There’s a room specifically for inserting primers into brass cartridge cases. These rotary machines feed empty brass cases into a priming mechanism where primers are inserted. It’s stunningly fast and watching how many dump out of the chute each and every minute is mesmerizing. As a reloader, consider me infinitely jealous.

The “tray” loading system in action.

The Sig team has chosen to use a tray loading system. Rather than sending cartridge cases down a production line individually, 210 cases are loaded into a tray and cartridges go through the steps in bulk. The company loads handgun and short rifle (like 300 Blackout) cartridges this way. In the photo above you can see a tray being loaded with empty brass cases. The trays are shaken so that the brass cases fall into holes heavy (base) side down. From this point on, each tray goes all the way through the system until the final packaging stage.

Bullets, meet cases.

At the beginning of the reloading line, other trays are loaded with projectiles. In the seating stage, the two trays are mated temporarily to line the bullets up with the powder-charged cases.

Seating and crimping machines.

After a tray of cases is filled with powder, again all 210 at once, it heads to the seating and crimping machines. Two setups like the one above precisely seat and crimp all cases in a tray at once. At each step in the process, custom-designed checking systems verify things like primer presence, primer orientation, powder charge, case height, overall cartridge height, and more. There’s lots of redundancy in the verification systems, so any given cartridge will have similar attributes checked multiple times throughout the process.

The packaging stage.

Maybe I’m easily amused, but the part of the process that got my attention was the packaging setup. Guides, pulleys, belts, and vacuum machines guide trays of cartridges into boxes, orient them, seal them, and print labels. It’s mesmerizing and runs without a hiccup for thousand and thousands of boxes of ammo per day.

This brass “cup” is about to become a 6.5mm Creedmoor case.

One of the reasons that Sig Sauer moved into a giant new factory was to add a brass-making production line. As volumes increase, the company needs to be in control of its own brass case supply. The new brass production line is making the rifle cases for now. On the day I was there, that line was cranking out billions and billions (OK, maybe that’s a slight exaggeration) of 6.5mm Creedmoor cases in advance of launching that new caliber.

One of the many brass forming presses.

Sometimes the old ways are the best ways. The company has scoured the country in search of these No. 304 machines because they’re the best. To bring them up to date, they’ve added custom computerized control systems. You’ll see a line of these where each machine does a little more work to each case, ultimately turning it into a completed cartridge case. One of the unique things about how Sig does it is that they wash and tumble the brass at each step along the way, so every case gets a half-dozen or so cleanings along the way. It’s not required, but the Sig folks have found that the extra work yields a more consistent end product.

The custom annealing machine.

Towards the end of the brass line is a custom brass annealing machine. This setup heats each piece of brass around the shoulder to make it slightly more flexible rather than brittle. That allows the seating process to work smoothly while maintaining the right amount of case neck tension on the bullet.

A rifle cartridge reloading press.

Many of the rifle cartridges are loaded in a more traditional rotary press system like the one above. There’s a lot changing on a daily basis, so we may see something different in the not-so-distant future.

The arsenal.

When you do as much testing as Sig, you need to have a boatload of different guns. The arsenal room is chock full of rifles, revolvers, and pistols. Yes, you heard that right. Revolvers. Most of the guns here are made by different companies because Sig’s ammo has to work right with everything. What you can’t see in the photo is an empty rack for .44 Magnum revolvers on the left. The day I was there the indoor ranges were taking lots of abuse from that caliber.

Leave A Comment