When you can’t even see the target with the naked eye, that’s serious long range.

Long-range shooting is absolutely addictive. It’s a combination of math, science, and art. Mix all those things in the right proportion, and you’ll get the satisfaction of a first-shot hit at longer distances than most people walk in a day.

Here are a few things to know to get repeatable positive results when ranges are measured by fractions of miles.

Bullets don’t go “up.”

There’s a myth that just won’t seem to die. Lots of folks talk about bullets going “up” as they exit the muzzle. Well, they sorta do, but only because the bore is aimed “up” just a little bit as the shot is fired. If your rifle bore is lined up exactly parallel to the earth, the bullet will start to fall the very microsecond it leaves the barrel and will continue to do so until it hits the ground. It will never rise under these conditions.

The “up” misunderstanding comes from the fact that the scope and bore are actually angled slightly towards each other. If the scope is pointed at a distant target and exactly level with the earth, the bore is actually aimed just a bit upwards. As the bullet is always falling, the shooter needs to aim “up” just a bit so that it will impact the target and not the ground in front of it. It’s just like throwing a football – the farther the receiver, the more you have to lob the ball to get there.

Mastering gravity is pretty easy.

For really long shots, you have to account for a lot of bullet drop. As an extreme example, when I attended the NRA Outdoors Long Range Hunting course, we got inspired to shoot at a small bush in the middle of sandpit that was 1,400 yards down range. For some long range rifles, that’s not really a big deal. However, we were using stock Smith & Wesson AR10 rifles with standard 168-grain .308 Hornady A-Max ammo. This combination really isn’t designed for shots past three-quarters of a mile, so it was adventurous to say the least. Using our Kestrel AE ballistic computer weather meters, we figured the shot required 65 minutes of angle of elevation adjustment. In English, that means we had to aim exactly 946.4 inches above the target to get a hit. Yes, just under 1,000 inches, or about 28 yards. That’s quite a lot of adjustment and sounds hard, but it’s actually not, provided you hold steady and focus on a smooth trigger press. That’s because gravity is really, really predictable. As long as you know the atmospheric conditions and the exact velocity of your round from your specific rifle, you can calculate the required hold over pretty easily.

The bottom line? Gravity always wins, but at least it’s predictable.

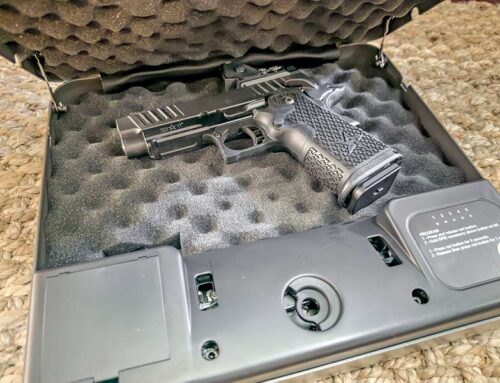

Stability is everything. We got great results with this Smith & Wesson M&P 10 from the prone position with a bipod and sandbags.

Never Mind.

I guess you rejected my previous comment.

Hmmm. Spam filter must have grabbed it. Will check it out.

What scopes do you all favor? A lot of guys recommend the Nightforce, but not all are willing to pay the price for one. Any cheaper alternatives you recommend?