This article originally appeared at Ammoland.

These Aero Precision barrels are identical, except for length. Same steel, same manufacturing, same rifling.

Of all the things you agonize over when choosing an AR-type rifle, should barrel length be on the list? How much does it matter whether you choose a 16, 18, or even 20-inch barrel? If you buy the wrong one, will you fail to ever hit another target? Will the bullet even make it out of the fiery end before falling to the ground? Will General Mad Dog Mattis ever compete on Dancing With The Stars? Here, we’ll explore the answer to these, and more, important questions.

Just to set the stage, we’re talking about service rifles here, not fancy bench rest stuff where competitors have to call their shots for either the right or left eye of a mosquito or other ectoparasite at distances of 800 yards. So, in the context of recreation and defensive use, let’s take a look at the impacts (or possibly lack thereof) of choosing from the most common barrel lengths. With just one “just for fun” exception, we’ll stick to barrels that are available without the need for sending Uncle Spendy extra cash for tax stamps: 16, 18, and 20 inches.

Before we get into testing, some background info is in order. There are two big factors that impact velocity of a bullet.

First, in a perfect, frictionless environment, as long as the pressure behind the projectile is increasing, the bullet’s velocity will also increase. Certainly, the powder charge type and burn characteristics will have a major impact on how long pressure continues to increase. However, barrel length also comes into play. In a fixed volume environment, as long as the burn reaction continues, pressure will build. But in a rifle barrel, the volume available constantly increases as the bullet moves down the bore. Think of the space as the inside of a tube that gets longer and longer. At some point, the rate of volume increase will exceed the rate of pressure increase. At this point, there is nothing that is making the bullet move faster.

Second, we have to consider friction. It takes a lot of work to jam a bullet through a barrel. If you don’t believe me, try hammering one through a bore with a wooden dowel sometime. The bullet is deliberately undersized relative to the bore so that the jacket will engage the rifling and impact a spin. It also must be undersized to provide a seal for the expanding gas, so none “slips by.” That would reduce pressure and lower velocity as well.

While variables are infinite, you can assume that it takes somewhere between 220 and 410 foot-pounds of energy for an “average” .223 bullet with a weight between 55 and 60 grains to overcome friction forces and exit the barrel. Put differently, if the energy in the cartridge only offered 300 or so foot-pounds of energy, then the bullet would barely make it to the muzzle and fall to the ground. OK, there’s more to it than that, but I want to illustrate the fact that friction is a big deal. Adding length to the barrel subjects bullets to more friction, so at some point, there will be too much friction from barrel length and velocity will start to decrease as you add more inches.

All this is a long way of saying that there are diminishing returns at play when it comes to getting more velocity out of a longer barrel. At some point along the barrel length spectrum, you’ll start to get less velocity. In reality, that point of diminishing return happens with a barrel longer than most commercially available ones.

I wanted to see how much of a difference there is between the most common lengths of AR-type rifles. To minimize variables, we decided to get our hands on samples of identically made barrels in three different lengths. To make sure everything was the same, we contacted the folks at Aero Precision and asked to borrow the following AR uppers; all chambered 5.56mm NATO.

Upper Receiver: AR15 20″ 5.56 Complete Upper w/ Pinned FSB & A2 Handguard

Upper Receiver: M4E1 18″ 5.56 Rifle Length Complete Upper Receiver

Upper Receiver: 16″ 5.56 CMV Barrel w/ Pinned FSB, Mid-Length / COP M4 Upper

As you can see, these Aero Precision barrels are identical except for length. They’re made in the same shop, from the same steel, using the same techniques. In case you’re wondering, they’re all button rifled.

Again to keep as much as possible constant, I used this Springfield Armory SAINT lower for all testing with all uppers.

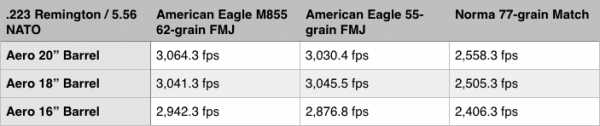

Velocity results

Using the same lower, I proceeded to shoot a boatload of ammunition through each barrel to measure velocities. I set up a Shooting Chrony Beta Master Chronograph 15 feet from the muzzle and did all the shooting on the same day, so the temperature was not a significant variable.

So what can we conclude from all this? For the most part, as expected, as the barrel got shorter, the velocity decreased. There was one anomaly that stumped me a little. Notice that the American Eagle 55-grain FMJ ammo INCREASED velocity when I moved to the shorter 18-inch barrel from the 20-inch version. I figured this was a measurement error. Since it’s practice ammo, the velocity varies more than with match ammo, so I shot a ton more. Guess what? No change in results. Average velocity was always greater, with this specific ammo, when fired from the 18-inch barrel as compared to the 20-inch one. Weird science

I tested velocity all on the same day, using the same Shooting Chrony Beta Master setup to minimize variables.

There are some interesting observations if we take a closer look at the numbers. You see the following effect with all three ammo types, but let’s zero in on the Norma match ammo since the velocities in any rifle are consistent. When moving from a 20-inch barrel to the 18-inch, the velocity decreased by about 52 feet per second. If we assume things are linear, that equates to 25 feet per second per inch of barrel length. If you’ve heard the “rules of thumb” about velocity and barrel length, that’s about what we would expect. Now look at the difference between the 18-inch and 16-inch barrels. Velocity decreases by nearly 100 feet per second or 50 feet per second per inch. That’s a big change, right? It’s not a fluke as we see similarly dramatic drop offs with the other two ammo types as well.

For velocity and accuracy testing, I used a combination of everyday ammo like American Eagle 55-grain FMJ and M855 Steel Core and Norma 77-grain Match ammo.

So why does this happen? It’s almost certainly not because the “powder didn’t have enough room to burn.” Generally speaking, all the powder THAT IS GOING TO BURN does, in fact, burn in the first few inches of barrel length. What it does tell us is that the gas cloud is still expanding faster than the volume of the barrel is increasing when the bullet exits a 16-inch barrel. In other words, pressure is still building when we run out of barrel in the 16-inch rifle, so some of that pressure is wasted. There is one other variable that probably contributes to this difference. On the 16-inch barrel, the gas port is closer to the chamber, so gas is vented earlier in the process.

Just for kicks, since I had access to an 8-inch Aero 300 Blackout short barrel, I decided to test that against a standard 16-inch barrel. I didn’t have an Aero 300 Blackout in that length, so I compared against a Daniel Defense DDM4v5 300 Blackout rifle. Both the eight and 16-inch barrels had 1:7 twist rates, although they were made by different manufacturers using different techniques. The Aero barrel is button rifled while the Daniel Defense is cold hammer forged, so understand that materials and method of manufacture might be responsible for some of the velocity variance too.

With the 125-grain supersonic load, the velocity loss going from a 16-inch barrel to an 8-inch barrel was about 255 feet per second or 31 feet per second per inch. With the subsonic load, there was only an 80 feet per second total loss or about 10 feet per second per inch. That surprised me a little bit. If you’re going to shoot mostly subsonic ammo in a 300 Blackout, you might as well consider a short barrel.

If you’re going to use a 300 Blackout primarily with subsonic ammunition, I see no reason not to use a short barrel like this 8-inch Aero Precision model. The folks at Silencer Shop lent me this Gemtech 300 Blackout suppressor for testing.

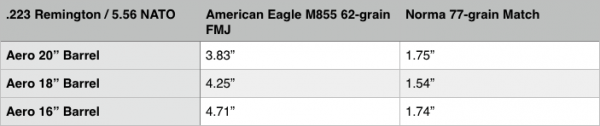

What about accuracy?

For accuracy testing, I used a concrete bench supporting a Blackhawk! Titan rest weighed down with a 25-pound bag of lead shot – plenty stable!

While I was at it, I decided to do some accuracy comparisons. I set up targets at 100 yards and proceeded to shoot a ton of five-shot groups with the American Eagle M885 and Norma 77-grain Match ammo. I used the same Burris XTR II 2-10x optic and moved it to each upper in turn. I shot from a Blackhawk! Titan rest weighed down with a bag of lead shot and used a rear bag for stock support. All this gave me a solid shooting platform which removed as much shooter error as possible. After shooting multiple five-shot groups with each combination of barrel and ammo, I averaged the group diameters to see whether barrel length had any impact on accuracy. Since I was running low on the American Eagle 55-grain FMJ, I limited my accuracy testing to the M855 and Norma Match.

Theories on the results? Looking at the M855, I could guess that the longer barrel MIGHT have stabilized a less than perfect round a little better. Admittedly, that’s a weak theory. Typically if the twist rate is right to stabilize a bullet, extra barrel length doesn’t really matter. If you forced me to explain the progressive decrease in accuracy of the M855 as the barrel got shorter, I’d bet a maple-glazed donut that it’s just ammo variance. I’ve not found M855 to be very consistent in any rifle, so odds are pretty good we’re just seeing some randomness.

As for the Norma 77-grain Match ammo, note how accuracy of the barrels at the two extremes are almost identical. That is interesting, and supports the theory that once a bullet is stabilized in the first few inches, the rest doesn’t really matter. As for the 18” barrel and it’s better accuracy? I’d guess that particular one is just a slightly smoother and polished bore than the other two. To me, the big learning is that the 16-inch barrel, with a whopping four inches shorter length, was just as accurate as the 20-inch version when using quality match ammunition.

So what’s the bottom line?

I’m not the only one to observe that extra barrel length really doesn’t improve accuracy on its own. If you’re after a super-accurate rifle, get the length you prefer for handling and spend the money on barrel quality.

As for velocity, here’s how I might approach the situation. Rather than pondering raw velocity numbers, think about your application. If you’re hunting two or four-legged critters, you might want to consider the range at which you need your bullet to be effective and work backward from there. Here’s what I mean by that.

Say you want 500 foot-pounds of energy at the target, and you’re shooting that 62-grain M855 projectile. When you use the 20-inch barrel, the muzzle velocity will ensure that you have 500-foot-pounds to just past 415 yards. If you shoot the same bullet from a 16-inch barrel, you’ll all below 500 foot-pounds at 375 yards. Or you could look at the point where the bullet crosses the supersonic threshold and starts to lose accuracy. For the 20-inch barrel, that will happen at 830 yards. For the 16-inch barrel, that happens at 775 yards. OK, not a huge difference either way, but that’s how those differences in muzzle velocity translate for energy and supersonic performance down range.

Those down range performance differences aren’t all that dramatic, so unless you have very specific needs, get the rifle you like, regardless of barrel length. In most scenarios, it’ll do what you need.

About

Tom McHale is the author of the Insanely Practical Guides book series that guides new and experienced shooters alike in a fun, approachable, and practical way. His books are available in print and eBook format on Amazon. You can also find him on Google+, Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest.

Your writing is brilliant and hilarious. You’re first among my bookmarks!

Thanks for the kind words Jeff!

That was a fun article to read! #FJB