This article originally appeared at Ammoland.

What better way to test out twist rate theories than using two identical uppers. These complete upper assemblies from Stag Arms feature 1:7 and 1:9 twist rates.

There’s more misunderstanding surrounding AR-15 barrel twist rates than the electoral college’s secret faculty lounge and doomsday bunker under the Denver International Airport. That’s because, as with any complex topic, there’s plenty of myth wrapped around some nuggets of truth. That blend of fact and fiction is what makes the topic mysterious to so many.

We decided to embark on a little experimentation to put some of the common assumptions to the test. When buying a common AR-15 barrel, what do you have to worry about given the type of shooting you intend to do? What types of ammo should you use, or not use, for your particular barrel? Will choosing the wrong twist rate for your AR-15 cause the moon to plummet into the Toad Suck, Arkansas State Park? With some help from our friends at Stag Arms, we decided to explore the topic a bit more.

What is twist rate?

As a quick level setting refresher, the twist rate of a rifle barrel refers to the speed at which the rifling imparts spin to the projectile. A more aggressive rifling pattern, represented by a faster twist rate, will turn the bullet more for each inch of travel down the barrel thereby resulting in a faster spin rate. With most modern AR-15 rifle barrels you’ll hear twist rate expressed in terms like 1:7 or 1:9. The first number refers to one full rotation of a bullet. The second number refers to how many inches of barrel length it takes to make that one full rotation. For example in a 1:7 twist barrel, the bullet travels 7 inches down the bore before it makes a full rotation. In a 1:9 twist barrel it takes 9 inches to turn the bullet around one full-time.

As a side note, I loved these Diamondback hand guards on the Stag uppers. Very cool!

Why is twist important and what can go wrong?

The goal of all this twisting is to stabilize a bullet in flight. Just like a football, a bullet has to spin to fly straight and true over distance. How fast it needs to spin to maintain perfect stability throughout its flight path depends on a whole lot of factors like velocity, bullet diameter, bullet weight, shape, and weight distribution within the bullet itself.

Here’s where things start to get weird. There are several theories about what can go wrong if twist rate and specific bullet attributes don’t match up properly. And like all theories, there’s usually some truth involved, and that makes the myths all the more persistent.

First, if a bullet doesn’t spin fast enough, it won’t be stable. Like throwing a football end-over-end, it will fly all wobbly, to the point of not really “flying” at all. The bottom line is that it won’t do what it’s designed to do – fly predictably. You may have even seen targets with oblong holes in them from a bullet impacting sideways. That can happen as we’ll soon see.

You might also hear about over-twisting a bullet. In theory, if you spin a given type of bullet too fast for its design parameters, it can fly apart in mid-air. It sounds crazy but think of this like a flywheel on a piece of mechanical equipment. If you spin it too fast for its construction and materials limitations, it will self-destruct by flying apart. If that example is too obscure, go out into your front yard, grab a friend by the arm and spin them around you as fast as you can. Eventually, they’re going to launch right into the neighbors recycling bin. In a less extreme scenario, an over-rotated bullet may self-destruct on contact with virtually any target, even a soft one, because it’s on the verge of coming apart at the seams.

I loaded some seriously goofy AR-15 rounds for this project. The things we do for science…

Twist rate considerations

For everything to work just right, you need to match bullet types and barrel twist rates. Normally people talk about bullet weight being the deciding factor. That’s not entirely true. For example, consider civil war rifle barrels. They might use twist rates as slow as one rotation in 78 inches to stabilize a heavy musket ball. The spherical shape makes them short for their weight, so a fast spin was not needed. The primary concern is bullet length, but that usually corresponds pretty closely with weight, hence the confusion.

Longer (and usually heavier) bullets require a faster twist rate because they tend to be more inherently wobbly. Shorter (and lighter) bullets don’t need as much spin to stabilize so slower twist rate barrels work fine for those.

When you buy an AR-15 chambered in 5.56mm NATO or .223 Remington, you’ll typically see one of the following twist rates on the barrel: 1:7, 1:8, or 1:9. While you might find other twist rates on certain rifles, like 1:12, those first three are now the most common. As a side note, you will see differences on bolt-action rifles in .223 Remington as those are often optimized for lighter varmint bullets. Here, we’ll stick to AR-15s.

The 80-grain bullets are too long for AR-15 magazines and had to be loaded singly into the chamber.

To clarify what’s real and what’s a myth we decided to do a little testing by loading up some bullets at the short and long extremes and firing them through two nearly identical STAG Arms upper receivers. We used the 3HT and 3HT+ uppers, ready to go with bolts, carriers, and the exceptionally badass Diamondhead VRS-T handguards. These barrels share the same construction method, were made in the same shop, and only differ by twist rate. One was a 1:7 twist while the other features the slower 1:9 twist rate. We didn’t bother with a 1:8 twist rate barrel because they’re designed to shoot everything, so that was unlikely to illustrate any odd behavior.

Safety First!

Experimenting with stuff like this can be dangerous. All loads concocted for this article were within published guidelines and shooting tests were done under controlled conditions. We did everything at a proper outdoor range and started from short distance so we could be certain that any unstable or fragmenting bullets were trapped by the very large backstop directly behind the target. As you’ll see, that turned out to be a good thing, as some load and barrel combinations proved uncontrollable.

Weird Science

I loaded up two different types of .223 Remington ammo at extreme ends of the bullet length and weight spectrum. Using all once-fired Lake City brass, I loaded a batch of ammo using Hornady 35-grain V-Max bullets for the short and light sample. These are stubby little bullets intended for bolt gun varmint loads, but we’re doing weird science, right? For the long and heavy sample, I loaded a bunch of Hornady 80-grain A-Max bullets. I should note that these bullets are not designed for semi-automatic use – the overall cartridge length is too long to fit in a standard magazine so they must be singly loaded in the chamber. The sacrifices I make for science…

I loaded up a couple of batches of .223 to represent the bullet length and weight extremes using Hornady 35-grain V-Max and 80-grain A-Max bullets.

With bullets and uppers in hand, I headed to the range to see what happens with these loads in various scenarios. I started everything at a short distance of 25 yards. If things were going to get weird right out of the muzzle, I wanted to be right up against a big backstop for safety purposes. The short range would also allow me to keep weirdly behaving bullets on paper so I could see what happened. Depending on short range results, I would move to the rifle range for stage two.

Here’s what happened.

1:7 twist rate, 25 yards, 35-grain bullets

This test the theory of over-rotation. I clocked velocity of these guys at an average of 3,216 feet per second using a Shooting Chrony Beta Master Chronograph placed 15 feet in front of the muzzle. Doing some quick math, I figured the revolutions per minute (RPM) of these rounds at about 330,788. That’s some serious spin considering your car engine screams bloody murder when it gets to 6,000 or so. To put in in perspective, the blades in a jet turbine spin in the range of 8,000 to 15,000 rpm.

Check out this non-group from 35-grain bullets fired from the 1:7 twist barrel at just 25 yards. Impacts spread across two 12-inch target squares.

I fired at a 12-inch square target 25 yards away and was lucky to be on paper. Five shots later, I walked out to inspect the target and found some pretty interesting results. My group, if you want to call it that, covered an area 14 inches tall and about eight inches wide. Not a single bullet hole was round, indicating either contact fragmentation from cardboard impact or perhaps weird tumbling. I suggest fragmentation because the target showed evidence of fragments hitting the paper separately from the primary holes. The other clue was that the holes weren’t “keyhole shaped” as we saw later in the test, but jagged, random, hot messes, kind of like a Kardashian family reunion.

Not only did bullets fly all over the paper, there was evidence of mid-air fragmentation. The bullets that did make it to the paper either blew up on contact or hit really weird. All the holes were ragged and random.

Given the randomness of the short range performance of these short light bullets from a 1:7 twist rate barrel, I had to stop at 25 yards because bullets would have never stayed on the backstop from 100 or more yards. If you want to hit absolutely nothing, this could be an option!

1:7 twist rate, 25 yards, 80-grain bullets

This combination worked just fine. I clocked velocity at 2,541 feet per second and proceeded to shoot at the 25-yard target. This combination of long and heavy bullet with a fast twist rate barrel was supposed to work, and it did. Bullets went right where they were supposed to, made nifty perfectly round holes, and grouped nicely.

By the way, the rpm of these bullets are about 261,360.

As expected, the 80-grain bullets worked as expected from the 1:7 twist barrel at 25 yards.

1:9 twist rate, 25 yards, 35-grain bullets

This combination was probably supposed to work also. I only say probably because these teeny, tiny bullets are most likely better suited for bolt gun barrels with a 1 in 12-inch twist or something along those lines. As it turned out, the 1:9 Stag Arms barrel worked just fine, at least at 25 yards. The bullets made a one hole group with nice round holes and impacted where the scope said they would.

Since we got all math geeky with the 1:7 barrel, I’ll mention that this combo spun the bullet at about 257,280 rpm.

As expected, the 35-grain bullets worked like a champ from the 1:9 barrel at 25 yards.

1:9 twist rate, 25 yards, 80-grain bullets

According to the warnings from ammo and rifle manufacturers, this is not supposed to be a workable combination, but in the name of science, I wanted to see exactly what happened. As ESPN’s Chris Berman would say, we had some rumblin’, bumblin’, stumblin’ bullet performance. My 25-yard group measured about 10 inches wide by six inches tall. The best part was the nifty bullet profiles in the target. Every single bullet impact made an oblong, bullet-shaped hole, just as if the rifle tried to launch them completely sideways. Clearly, as soon as these lumbering 80-grainers left the barrel, they started to tumble end over end. Interesting, but probably not very useful for long range precision shooting. Needless to say, I had to end this particular combination at the 25-yard range as well as there was no telling where bullets would fly on the longer rifle range.

The long and heavy 80-grain bullets were all over the target at just 25 yards.

Our spin rate for this final combination was somewhat leisurely, operating at just 203,280 rpm.

Every 80-grain bullet tumbled when fired from the 1:9 twist barrel at just 25 yards.

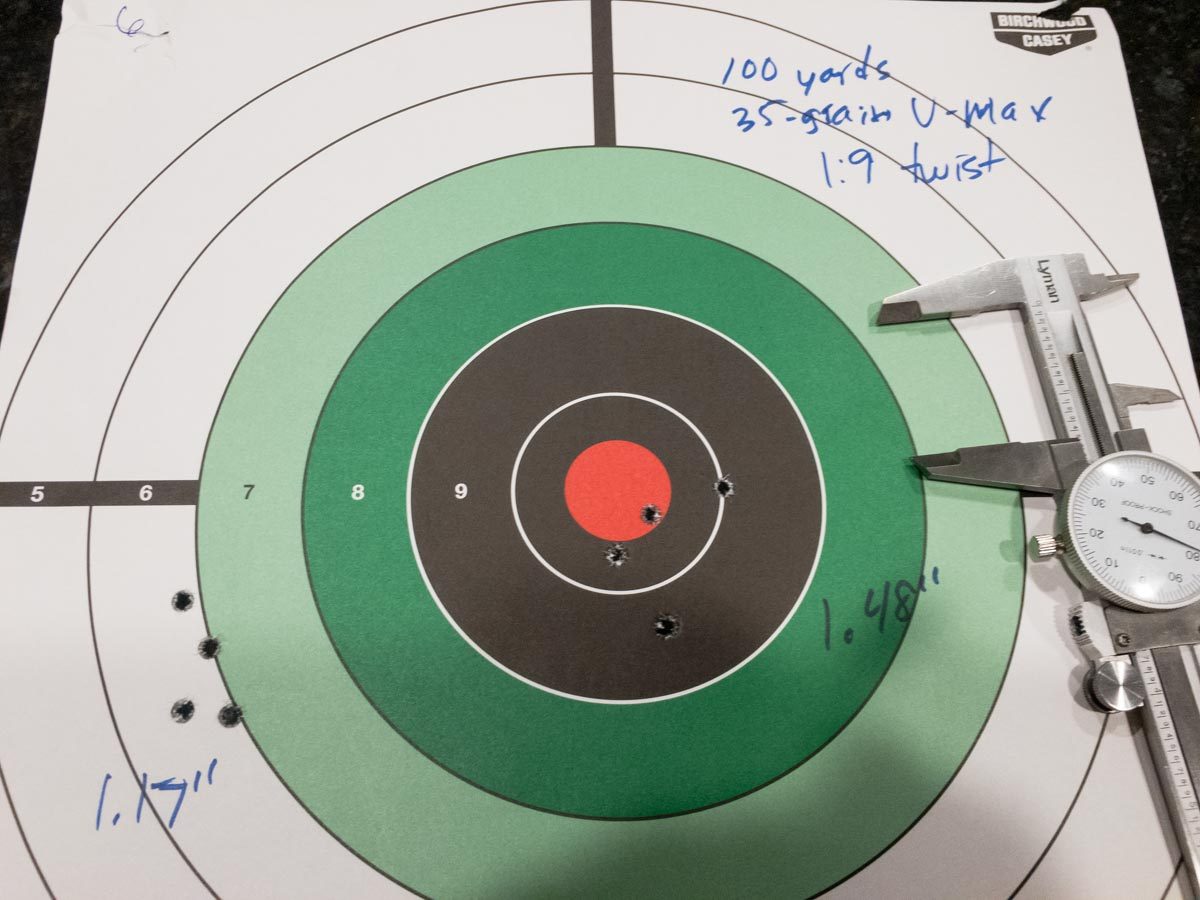

1:9 twist rate, 100 and 200 yards, 35-grain bullets

At 100 yards, the light bullets in the 1:9 twist barrel worked reasonably well. Two different five-shot groups fired from 100 yards measured 1.17 and 1.48 inches. I also shot these at 200 yards. It was a windy day, so that might have impacted group sizes a bit.

The 35-grain bullets shot well at both 100 and 200 yards from the 1:9 twist barrel.

Even on a windy day, I got decent groups from the 35-grain bullets at 200 yards from the 1:9 twist barrel.

1:7 twist rate, 100 and 200 yards, 80-grain bullets

Groups using the extra-long 80-grain A-Max bullets were predictable if not small. At 100 yards, I was getting 3.12 inches center to center and at 200, a little better with 4.83 inches. From the 1:9 barrel performance, I know the Stag Arms barrels are capable of solid accuracy, so I would guess it was my particular load combination that opened the groups a bit. With a dozen or so powders and hundreds of charge weight, powder, primer combinations, I’m sure I could have found a good load that generated better accuracy. But since the goal here was to see if the combination of bullet and barrel yielded predictable performance, I didn’t go down that road. The bullets were predictable using the 1:7 twist barrel as they were supposed to be.

Groups at 100 yards were predictable with the 80-grain bullets. Since this test wasn’t about accuracy, I didn’t spend any time experimenting with different powders or charges.

Summing things up

As a quick and dirty “control” I also shot Sig Sauer 77-grain match ammo through both barrels at 25 and 100 yards to see how the more commonly available ammo worked. At 25 yards, the 1:7 twist rate barrel shined, creating a near one-hole group just where expected. Using the 1:9 twist barrel, which is NOT recommended, I had some vertical stringing at 25 yards, but things weren’t completely random, so I felt confident shooting at 100 yards too.

Moving out to the 100-yard range, the 1:7 barrel gave me a perfectly normal 1.58-inch group with the Sig Sauer 77-grain ammo. Four of the five shots were touching, so the flyer that opened the group up to 1.58 inches might have been shooter error. Using the 1:9 barrel, I got a perfectly normal group as well, with three shots measuring .66 inches. I didn’t want to press my luck in case there was any weird performance, so I only shot three, checking each one. Again, this isn’t a recommended configuration, so don’t replicate it at home.

You’ll notice that I didn’t shoot any 55-grain bullets in either barrel. That’s because they’re middle of the road in terms of weight and length and will work just fine in any of these barrels. I’ve billions and billions of 55-grain bullets of varying types through 1:7, 1:8, and 1:9 barrels and not yet seen weirdness in any of them.

With the right bullets matched to the right twist rate, the Stag Arms barrels will shoot as shown by this control group using 77-grain Sig Sauer Match ammunition.

I should note that I wanted the shortest and lightest bullets I could find for this test, and that turned out to be Hornady V-Max. These are designed to have light jackets and blow up on contact with varmints, so they’re (again by design) more likely to blow up mid air when over-rotated. I’m sure there are short and light bullets out there that would not self-destruct when fired through a 1:7 barrel.

You can’t blame everything on the barrel. Non-concentric bullets are going to exhibit more random behavior at the edge of stabilization parameters than quality bullets that are perfectly balanced.

If you’re going to buy an AR-15 chambered in 5.56mm NATO, it’s hard to go wrong with either a 1:7 or 1:8 twist barrel for standard shooting. Those will handle a wide range of bullets safely. If you know you’re going to buy or build a varmint rifle, and you’ll be using light bullets, then you might consider one with a twist rate designed for the task, either a 1:9 or maybe a 1:12. Just be aware that if you go beyond 1:8, you’ll be limited to shooting bullets less than 60-some grains. As a practical example, I’m not a varmint guy, so all of my AR rifles are either 1:7 or 1:8 twist and I regularly shoot bullets from 50 to 77 grains with no ill effect. But once again, remember, it’s the bullet length, not the weight, that matters. Weight is just an easy way to categorize by approximate length.

Ain’t science fun?

About

Tom McHale is the author of the Insanely Practical Guides book series that guides new and experienced shooters alike in a fun, approachable, and practical way. His books are available in print and eBook format on Amazon. You can also find him on Google+, Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest.

Leave A Comment