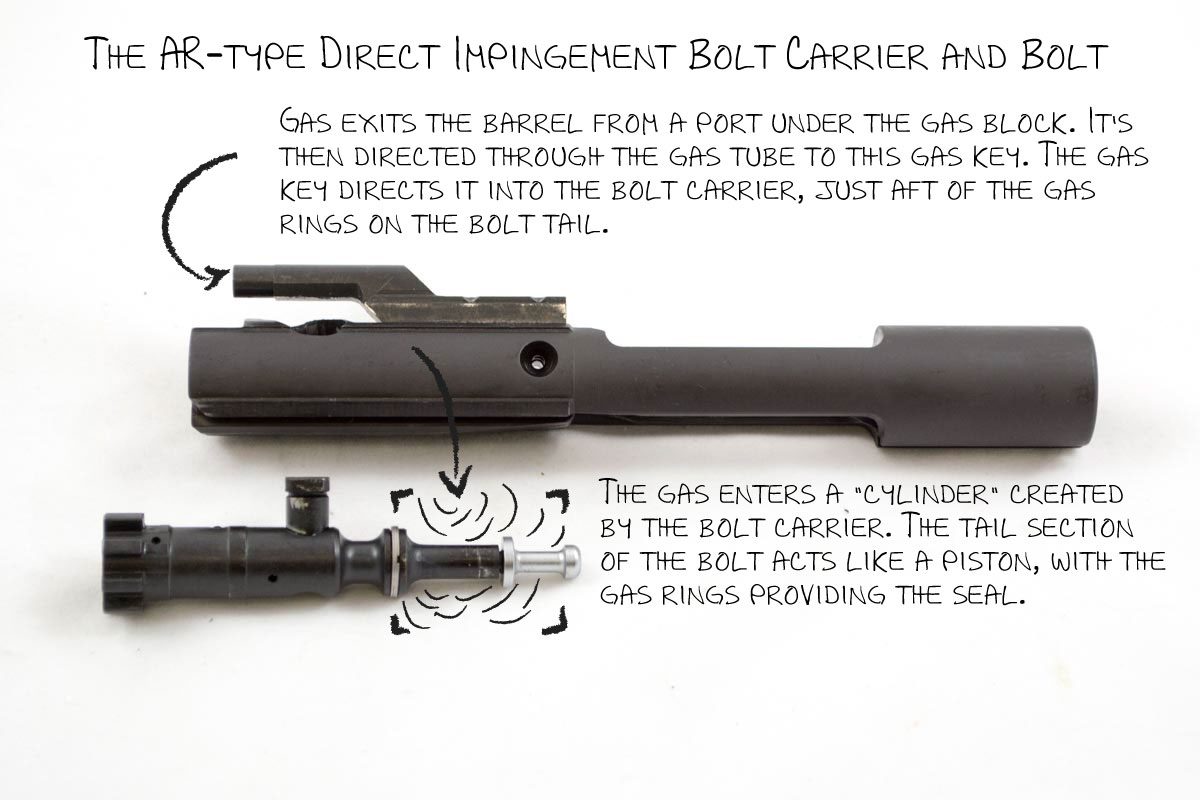

Imagine the bolt (below) inside of the bolt carrier (above) and you can see how the gas flow works.

All AR-type rifles have plenty of gas; they just deal with it differently.

Eugene Stoner had plenty of gas. So much so that he designed his AR-15 semi-automatic rifle to work entirely on gas flow. The method of operation was called direct impingement. Well, people refer to it as direct impingement, but it’s really a little bit different. We’ll get into that nitty gritty minutia in a bit. For now, just envision those nifty lug wrenches at tire stores that are powered completely by compressed air. It’s a similar concept.

But, as a fellow gun person, you know how we like to tinker. It doesn’t matter if something works or not; we’ve just got to tweak modify and try to improve things. Our collective experimentation has created another type of system for AR-type rifles. That would be piston operation. We’ll explain that in detail in a bit also.

Direct Impingement Operation

I’m going to use the term “direct impingement” here, but only because everyone else does, and it’s commonly known. Technically, Eugene Stoner’s original design is really more like an internal piston that operates inside the bolt carrier. Think of this comparison, and we’ll keep our analogies a little loose for simplicity.

In a pure direct impingement scenario, imagine blasting a jet of compressed air at a lever, like maybe a light switch. With enough air pressure, you’re going to bash the switch hard enough to move it to the opposite position. That hammering like motion with gas it sort of like true direct impingement.

With an internal pistol system, you’re filling the inside of a piston with compressed gas. As pressure builds, it’s gonna want to move the piston in the direction of least resistance. Again, with a slightly inexact analogy think of this scenario like a gas engine piston moving as the gas vapor ignites and increases the pressure inside of the cylinder.

Let’s look at exactly how this “direct impingement” or “internal piston” works in an AR-type rifle.

When you fire a cartridge, a veritable boatload of hot and expanding gas pushes the bullet down the barrel. It’s under really big pressure, starting at somewhere around 60,000 pounds per square inch. Of course, that pressure level rapidly declines as the volume between the cartridge base and bullet rapidly increases as the bullet moves down the barrel. The section of the barrel between the chamber and bullet at any given microsecond represents the available volume. And from high school physics, some famous smart guy stated that as volume increases, pressure has to decrease, all else being equal. I think it was Ben Cartwright before he opened a ranch on Bonanza.

Part way down the barrel (the exact position varies depending on the “gas system length” of the rifle in question) there’s a tiny hole that lets gas escape into what’s commonly referred to as the gas block. In original AR-type rifles with the triangular fixed sight, the gas block is contained within the sight assembly, so you really don’t see it as a separate piece. Part of the function of the gas block is to redirect some of the gas back towards the action of the gun. The gas is moving towards the muzzle, then straight up through the hole in the barrel. The gas block redirects it through a gas tube that leads back to the receiver. If you look through holes of the hand guard on an AR-type rifle, you’ll see a (usually) silver tube running between the front sight or gas block and receiver.

On a direct impingement AR-type rifle, the gas tube connects to the gas block and/or front sight and directs gas back to the bolt carrier group in the receiver.

This tube ends at what’s called the gas key on the bolt carrier. The key fits over the gas tube and redirects the gas into the interior of the bolt carrier where it can move the bolt itself. Here, the bolt and carrier act pretty much like a piston (the bolt tail) and a cylinder (the bolt carrier.) The gas enters the bolt carrier and fills a chamber created by the space between the gas rings on the bolt and the internal wall of the bolt carrier where the firing pin body is located.

As gas enters this “cylinder” area, it pushes the bolt in the direction of least resistance, which is actually forward. In the locked position, the bolt is pressed all the way into the bolt carrier. The expanding gas moves it forward, and the bolt rotates as the cam pin follows the angled path of the cam pin slot. Once the bolt partially turns and unlocks from the barrel extension, it has nowhere else to go, so the gas pressure inside of our “cylinder” pushes the bolt carrier backward towards the recoil spring. The bolt carrier movement drags the bolt with it, causing ejection of the round.

At some point, the resistance of the buffer spring overpowers the declining gas pressure and starts to move the whole assembly forward again, picking up a new round in the process. The bolt carrier and bolt slam into the barrel extension and pressure pushes the bolt back inside of the bolt carrier, rotating due to the cam pin slot. The bolt locks into position, and you’re ready to fire another shot.

That’s quite a lot happening in a small fraction of a second. In the context of direct impingement versus piston operation, it all boils down to this. The bolt itself is a piston. The bolt carrier is a cylinder. Rather than a “gas jet bashing motion” the operation is a more gentle expansion in a cylinder that results in movement. Of course, “gentle” is a relative term. Hot and dirty gas flows directly into the bolt assembly causing movement, extraction, hammer re-cocking and chambering of a new round. Don’t let the “hot and dirty gas in the bolt” concern you too much, as it’s a largely self-cleaning system. I don’t mean you don’t have to clean your rifle. I simply mean that gunk doesn’t build up infinitely on the interior of the piston and cylinder surfaces.

Leave A Comment